Labour's lobbying problem

"I’d be shocked if there isn’t a lobbying scandal in the first year"

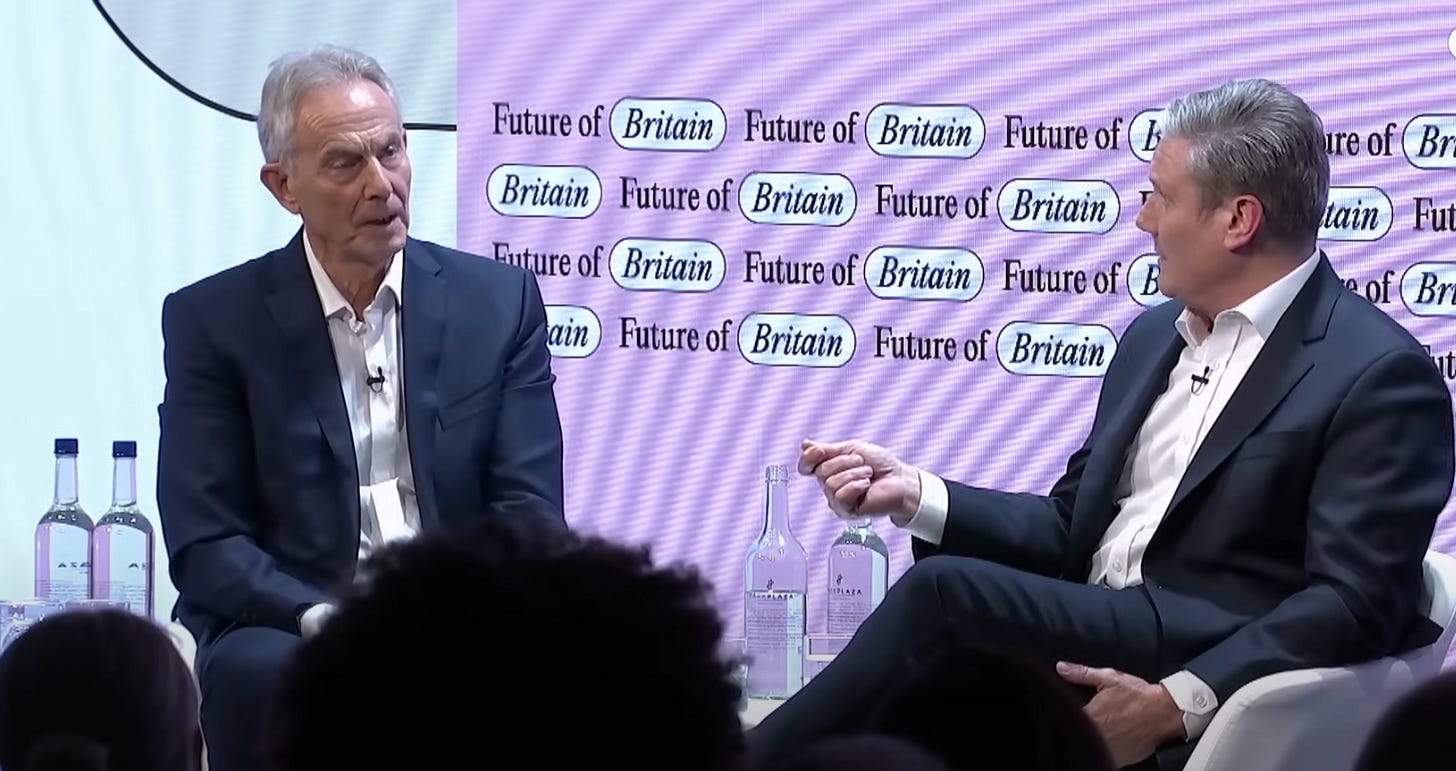

Keir Starmer and Keir Starmer at Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, July 2023.

During the general election campaign, Keir Starmer positioned Labour as the alternative to years of Tory sleaze.

Starmer was right: the Conservatives’ presided over unprecedented levels of corruption and cronyism in British politics. We are all still recovering.

But Starmer’s Labour has also sought to build very close links with the business lobby - and seems wary of upsetting party donors.

The King’s Speech had little to say about the revolving door between government and the private sector, donors buying access or foreign funding of political parties.

This week I’ve written a 4,000 word piece for the London Review of Books on Labour’s increasingly cosy relationship with the lobbying industry, the key players and why it’s in the party’s interest to take big money out of British politics.

The full essay is here (do read!) but I thought it was worth highlighting some of its key points.

The lobbying industry has become deeply enmeshed in British politics

A fifth of the Conservative MPs newly elected in 2019 had worked in lobbying or public relations. At least 34 of the new Labour MPs in this Parliament have a background in public affairs. Some have worked for charities and non-profits: Jacob Collier, the 27-year-old member for Burton and Uttoxeter, was a communications officer for Nottinghamshire Fire and Rescue Service. Others came from corporate lobbying companies: Chris Ward and Joe Morris, the new MPs for Brighton Kemptown and Peacehaven, and Hexham respectively, headed the Labour Unit at Hanbury Strategy, a firm co-founded by Vote Leave’s head of communications and a former speechwriter for David Cameron, whose clients include Citibank, Spotify and Deliveroo.

More than four times as many lobbyists as teachers ran for Parliament in July, according to analysis by the New Statesman.

Labour has become very reliant on freebies from business

Private firms have given Labour £1.8million worth of secondments and pro-bono work since 2022. HSBC, NatWest, PricewaterhouseCoopers and a host of consultancy firms sent staff to work for shadow ministers.In the days before the general election, senior Labour figures reportedly asked various companies – engineering firms, tech companies, management consultancies – to send more staff to help with policy work. Jim Murphy, the former Scottish Labour leader turned lobbyist, has praised Starmer’s ‘openness with the private sector’, predicting that this will be ‘the first private-sector government in Labour’s history’. A left-wing Labour MP complained to me that ‘business is running the show and Starmer doesn’t realise that’s a problem.’

Transparency campaigners have already raised concerned about how close Labour is to private business interests.

3. Lobbyists from ‘the Labour family’ could be a particularly problematic

*A lot* of former senior Labour figures now run lucrative ‘strategic advisory’ businesses. Peter Mandelson’s (below) Global Counsel is valued at £30 million. Tony Blair has his ‘Institute for Global Change’. Two staff members from Jim Murphy’s firm Arden Strategies are now Labour MPs.

Onetime Blair health secretary Alan Milburn has been heavily tipped for a role in Starmer’s government. As Democracy for Sale recently reported, Milburn’s personal consultancy has made more than £8million, largely from advising private healthcare interests.

That’s not all.

A number of other former Labour MPs work as industry lobbyists. Michael Dugher is chair of the Betting & Gaming Council – an industry that has donated almost £400,000 to Labour since Starmer ran for leader. ‘I’d be shocked if there isn’t a lobbying scandal in the first year,’ a veteran lobby journalist who covered many of the biggest scandals in the last government told me. ‘You have so many people working on policies that could really conflict with their company’s clients. It could start to look really bad.’

Labour is now the party of big money in British politics

Starmer’s party raised more money during the election campaign than all the other parties combined.

A drive to boost private donations brought in £12 million from wealthy individuals and businesses in the first half of 2024, making it less reliant on funding from trade unions. Lord Sainsbury, who had left Labour during the Corbyn period, has donated £8 million since the start of 2023. Dale Vince, the founder of Ecotricity, has given more than £3.3 million since Starmer became leader. Gary Lubner, the former Autoglass boss, has donated £5.5 million.

Interviewed by

, in Good Chaps, his excellent recent book about corruption in British politics, Lubner says that ‘in a perfect world I don’t think there should be any bloody donations to political parties.’Democracy for Sale would strongly agree. But already there are signs that some Labour’s donors are exerting influence on policy: in the process of reporting this piece, a well-placed source told me that Labour decided not to propose a cap on political donations after a backlash from party donors….

Labour Together is ‘Labour’s first Super Pac’

Labour Together is probably the most important organisation in British politics that most voters have never heard of. Under the stewardship of of Morgan McSweeney, now head of political strategy at Number 10, Labour Together built Starmer’s leadership. It is also set to play a key role in the Labour government.

One of the most striking things about Labour Together is that it is independent of the Labour party and has raised its own funds - more than £4million so far, mainly from Labour donors. (It also broke electoral law under McSweeney’s watch by failing to declare £700,000 worth of donations and was fined £14,250.)

I spoke to a number of people who either are or have been involved in Labour Together, including Jon Cruddas, the former MP for Dagenham and Rainham, who was a leading figure in the organisation early on but left last year.

Cruddas told me that Labour Together has become a vehicle for “corralling some of the hot money around Labour. The best way to understand it is as Labour’s first Super PAC.”

Cleaning up British politics is not hard - and is in Labour’s own interests

Starmer should commit to cleaning up British politics - because it’s the right thing to do, but also out of enlightened self-interest.

Taking big money out of politics would hit the right hardest. Labour has far more members than the Conservatives, and still receives union affiliation fees. (Reform, a private company masquerading as a political party, has no members but does have connections to foreign networks of clandestine funding, particularly in the US.)

And here’s the thing: it wouldn’t be hard to clean up our politics.

Taking money out of the system would be relatively straightforward: limit individual donations to, say, £10,000 a year and lower the caps on spending; force political parties to check the true source of donations; ban companies from giving sums greater than their UK profits; increase fines for breaching electoral law. Much of the Conservatives’ dreadful Elections Act could be reversed, restoring the independence of the Electoral Commission (currently under government supervision) and ending a situation in which a person has to prove their identity before voting but not before running for office. The meagre sums provided to parties for policy formation could be dramatically increased, eliminating the dependence on big business to supply researchers and advisers. Alternative models for funding politics, from state support to matching small donations, could replace the current US-style scenario in which a handful of super-rich donors effectively bankroll the entire political system.

Will Starmer and Labour adopt these policies? Democracy for Sale believes they should and will keep pushing to clean up British politics.

If you aren’t already, become a paid subscriber to support Democracy for Sale’s work.

All parties get their snouts in the trough seems to be the only way to survive.

Let’s call this what it really is - bribery! Nobody gives money for nothing in return.